Once Upon an Island - A Historical Write-Up on Bintan by Karien van Ditzhuijzen

- Karien van Ditzhuijzen

- Jan 7

- 13 min read

Updated: Jan 14

This post was written by an external contributor. If you are interested in writing a guest post for our blog drop us a line here.

Words by Karien van Ditzhuijzen, images by Cempedak Island, Gilles Massot or generated by AI.

We were introduced to Karien through Jane's Tours when she hosted a walking tour for one of our Island Club Events in Singapore. Karien is a writer and licensed tour guide whose winding career has spanned chemistry and ice cream product development, community storytelling with migrant workers, multiple published books, and guiding visitors through Singapore’s many layered cultures, a city she has called home since 2012 after living in eight countries. In December 2025, Karien visited us on Cempedak and kindly offered to provide our guests with a sunset talk on the history of Bintan and the region. Below is the write-up of this talk.

Karien providing this talk over sunset drinks at the Dodo Bar. December 2025.

Once upon a time, in a kingdom right here … These are stories of different eras that together present a glimpse of the illustrious history of Bintan Island. They speak of mythical queens, royal court intrigues and colonial scheming.

Many tourists visit Bintan island for its sea and beaches, or for sports events, and most of them don’t realise the island has a rather fascinating history. These days, Bintan may seem like a quiet backwater, but it wasn’t always like this. At several points in time Bintan had a thriving port, one of the biggest in the region. Kings and queens ruled the island and beyond. With these stories, instead of diving into the sea, we will dive into the island’s history.

Bintan lies at the heart of the Malay world, which includes not only the Riau islands but the Malay peninsula, Singapore, and parts of Sumatra. Its story features sea nomads, royals from Sumatra, colonials from the Netherlands, the UK, as well as Bugis warriors from Sulawesi.

Let’s start at the beginning, before the intrigues start …

For thousands of years the islands of Riau have been inhabited by the Orang Laut – the indigenous people of the region. Orang Laut means ‘sea people’ as they are one with the sea – the Orang Laut traditionally live on their boats and know the Straits like the back of their hands. They fish, forage for molluscs on the tidal flats and help visiting traders navigating the treacherous waters around the Straits with its currents, reefs and sandbanks and sell them fish and fruits. They are ethnically different from the Malay people, who emigrated to the area much later, and had their own language and animist religion. Although many of them have now integrated into the general Malay population, there are still Orang Laut communities on Bintan.

Neither the Orang Laut nor the early Malay immigrants left written records, but we find mention of Bintan in other historical sources from the 13th century onwards. Both Arab and Chinese accounts mention a centre of power at Bintan in the 13th century; Venetian traveller Marco Polo calls Bintan ‘a great savage place’ and that ‘the forests are all of sweet-smelling wood’. The Melaka Strait which passes to the north of Bintan is the main thoroughfare between east and west, the sea road to China, so the region has always held key trading posts which attracted foreign visitors. From the 6th century onwards the Malay Maritime Kingdom had its stronghold here, though its main port and centre of power shifted around the region. From the 6th to 12th century it was called the Srivijaya kingdom and was ruled from Palembang, Sumatra.

Archaeological surveys suggest that in the 13th century Bintan was developed but more in-depth research would be needed to learn more. What we know of Bintan as part of the Malay world comes from the Salalatus Salatin or Sejarah Melayu, a 17th century manuscript that tells the history of the Malay world linked to the then royal family ruling the Johor Sultanate. It is part historic, part legends and myths, linking back the royal lineage as far as Alexander the Great, via underwater kingdoms and the Srivijaya capital of Palembang. Folklore has it Bintan was founded by a Javanese from Banten. Let’s see what the Malay annals have to say about Bintan.

The Queen of Bintan

There are many versions of the Malay Annals, which vary in detail, but they all mention Bintan is ruled by a queen in the 13th century. Local lore confirms this, at the foot of Gunung Bintan, the highest mountain of Bintan, sits a graveyard at Bukit Batu, of which one grave is said to be of Queen Wan Seri Beni of Bintan. Local people and the graveyard caretakers have many stories about this legendary queen that ruled Bintan, similar to those recounted in the Malay Annals. Surveys of the graveyard and its oral traditions have been undertaken that tell more about this fascinating woman. Further archaeological research could help us learn more about her and her life. We do know the region has a strong matriarchal tradition, particularly in Sumatra where the Malay migrated from, so to have a Queen rule Bintan in this era is not surprising.

Both local stories and the Malay Annals link Queen Wan Seri Beni to Sang Nila Utama, the Srivijaya prince who fled north after a Javanese attack on Palembang in the 12th century. The Srivijaya Kingdom had ruled the region since the 6th century but with the threat of the rising Javanese Majapahit Kingdom its rulers migrated north, spreading the Malay culture and language across the region.

Different versions of the story of Sang Nila Utama exist, but they agree he stayed in Bintan for some time. Queen Wan Seri Beni adopted him as her son (some versions have her or her daughter marry him). One day Sang Nila Utama saw the sandy beaches of Singapore and decided to move there to found the 14th century Singapura kingdom. Sang Nila Utama is seen as the legendary founding father of the Malay world and the Sultanates of the Malay peninsula. This makes Queen Wan Seri Beni, his adopted mother, its founding mother figure. She is mostly forgotten, but those who took a ferry from Singapore to Bintan might have noticed the names of two of the vessels: Wan Seri Beni and Wan Sendari, that honour two Bintan queens: Queen Wan Seri Beni herself and Wan Sendari, a princess from Palembang that came here as Sang Nila Utama’s wife and later gave birth to his heir.

Unfortunately, we don’t know more about these two important women in Sang Nila Utama’s life. What we do know is that the Malay rulers in Singapore were once again attacked by the Javanese and fled further north to found the Sultanate of Melaka, which became the most powerful city in the region, quite possibly the world. It stayed that until 1511 when the Portuguese took the city by force and the Sultans fled again, this time to Johor, where they settled along the Johor River. And this is where we start our second story relating to Bintan.

The Laksamana of Bintan

The Johor Sultanate had lost Melaka but still had strong trading relations with China and the Arabs, and in the 17th century with the help of the Dutch they ousted the Portuguese from Melaka. Unfortunately, the Dutch decided to keep the town for themselves. By the end of the 17th century the Malay port at the Johor River still ran a good amount of local trade. To protect the capital and port they had an army and fleet, which was based at Bintan, which sits near the entrance of the Johor River. The laksamana, a high noble rank similar to an admiral, resided in Bintan to oversee the fleet.

When the Sultan died his young son Mahmud ascended the throne, but as he was too young to rule the Bendahara, another noble rank that was in charge of domestic affairs, ruled as regent. When the powerful Bendahara died his son took over but by now young Mahmud started to exert his powers. He proved erratic, cruel and unfit to rule. The Bendahara and other high-ranking officials at court decided he had to go.

In 1699 Sultan Mahmud II was murdered. But killing a Sultan was not only treason, to the Malay the royal bloodline was sacred, dating back to the Srivijaya kingdom. Many stories surfaced to justify the killing of this young Sultan and the most popular one features none other than the Laksamana of Bintan. There had been rivalry between the Bendahara and Laksamana, who had established a power centre at Bintan and tried to become ruling regent himself. At court a jackfruit tree grew that was so special only the Sultan was allowed to eat it, at penalty of death. Then, one day, a piece was missing and the Sultan was livid. The laksamana’s pregnant wife was identified as the culprit but she claimed innocence, saying it wasn’t her but her unborn child who craved the fruit. The enraged Sultan sliced open her stomach and indeed, the baby was revealed with a piece of jackfruit in his fist. The laksamana’s wife might have been innocent, but both she and the baby died. The laksamana was not amused. He stabbed the Sultan, who stabbed him back, and both died. In Kota Tinggi in Johor the graves of the laksamana and his wife still stand side by side, a few miles from that of Sultan Mahmud II.

The murder of Sultan Mahmud II was significant. He had no heirs, no male brothers, cousins or uncles. He was the last of the legendary bloodline that traced its ancestry back to Melaka, Singapura and if we believe the Malay Annals, Alexander the Great. The Bendahara became the new Sultan but he lacked wide support, and the Sultanate was in turmoil. The Orang Laut, who always fought in the Malay fleet, deserted. When a usurper from Sumatra appeared, claiming descent from the late Sultan, they joined him and the Johor capital was in peril. Which brings us to the next story.

Five Bugis Princes

The Sultans needed help to fight off the attack. The Dutch in Melaka were not willing to help and anyway had proven an unreliable ally. They found another ally in five royal princes from further east.

The Bugis people come from East Indonesia, from the island of Sulawesi. They are seafarers, traders operating a huge fleet. They are famous shipbuilders and known to be fierce warriors. One of the famous ships they built are the Phinisi, a sailing ship with several masts. These days they are produced in luxury versions for tourists to take cruises around the archipelago.

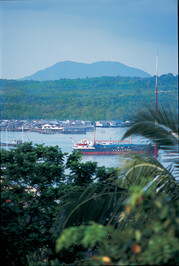

After the Bugis lost Makassar to the Dutch many of them moved to the Malay archipelago. In particular five Bugis princes that were famous warriors, and the Malay asked for their help to fend off the attack of Aceh. The Bugis saved the Sultanate but, like the Dutch before them, they also took power. The Sultan became a figurehead, and the Bugis Yamtuan Muda, or viceroy, held the real power. The Bugis moved the capital to Bintan where they ran the port at the river at Tanjong Penang, which again became one of the most prosperous of the region.

The Bugis kept quarrelling with the Dutch, attacking Melaka, and after a series of Bugis–Dutch wars the Dutch raided Bintan and banned the Bugis. They installed a Malay viceroy, another high-ranking royal called the Temenggong, who was traditionally in charge of the port and security. He tried to revive the port but struggled without the powerful Bugis and their trading fleet. The new Bendahara moved to Pahang on the peninsula. The Sultan retreated to Lingga, an island in the south of the Riau archipelago.

Then something happened far away, in Europe: Napoleon invaded the Netherlands. It is strange to imagine that something so far away had far-reaching consequences for the Malay world, as this invasion would set in motion a series of events that changed the fate of Bintan until now. The Dutch prince fled to London to ask the British to keep his possessions in the East safe, so the French wouldn’t get hold of them. Melaka and Java became British. With the Dutch gone, the Bugis returned to Bintan.

Our next story is about a Bintan princess trying to save her kingdom.

Raja Hamidah, Bugis princess of Bintan

After the Bugis returned at the end of the 18th century, the struggle for power in the Sultanate between the Malay faction and the Bugis viceroys continued. The last Sultan of a united country, Mahmud III living in Lingga, felt stuck between the two and tried to solve the struggle by marrying Raja Hamidah (also known as Engku Puteri), a famous Bugis princess. She was part of the most influential Bugis family, the daughter of a powerful warrior who died a martyr at Melaka, and the sister of the viceroy.

The Sultan gave his new wife a very special wedding gift: Pulau Penyengat, a small island in front of Tanjong Pinang, the capital of Bintan. The island had been used as a lookout and fort in the Bugis–Dutch wars but now became the residence of the Bugis viceroys, with both Raja Hamidah and her two powerful brothers settling there. The island still has many remnants of the Bugis times, and the graves of Raja Hamidah and her father can be visited, as well as several other landmarks that remember the era.

Unfortunately, Raja Hamidah had no living children. There was no obvious heir. Sultan Mahmud III, caught between the power struggle of the Bugis viceroy and the Malay Temenggong, decided to hedge his bets. He had two sons from non-royal mothers, and he gave the eldest, Hussain, as a ward to the Temenggong and the younger, Abdul Rahman, was put under the Bugis viceroy. Furthermore, Raja Hamidah adopted Hussain, his father’s preferred successor, as her son. Hussain’s mother is buried next to Raja Hamidah at Pulau Penyengat.

In 1812 Sultan Mahmud III died. Hussain was away in Pahang to solidify his ties to the Bendahara by marrying his daughter, and the Bugis viceroy seized the moment and quickly put Abdul Rahman on the throne. Raja Hamidah disagreed. She wanted to follow her late husband’s wishes and see her adopted son Hussain on the throne.

Raja Hamidah refused to hand over the royal regalia, and without them, the Malay did not accept the succession of Abdul Rahman to the throne. By many the succession was seen as not concluded.

Hussain wrote to the British in Melaka for help, but they declined to interfere in local affairs, and Hussain retreated from court. The Temenggong moved to Singapore. The Sultanate had split into four relatively independent fiefs: Bintan with its port under the Bugis viceroy, Lingga under the Sultan, Pahang under the Bendahara and Johor and Singapore under the Temenggong.

And then something happened again on the other side of the world in 1815: Napoleon was defeated at Waterloo.

The British needed to hand back Melaka and Java to the Dutch, who returned and signed an alliance that allowed no other foreign powers to settle in the area. But the British didn’t give up. They knew about the fragile position of the Sultan and the power struggles in the Sultanate. Particularly Farquhar, the popular resident of Melaka under the British, and Raffles, who had been resident in Java and was now sent to Bencoolen in Sumatra, an unpleasant backwater in a bad position for trade that he wanted to leave as soon as he could.

In 1818 the British approached the court in Bintan to ask if they could start a trading settlement in Bintan but were told no. Raffles didn’t give up easily and concocted a scheme. He sent a letter to the court claiming that the Dutch planned to attack Bintan and take over the port. The Bugis, who had long quarrelled with the Dutch, believed the lie and signed a treaty with the British. But the Dutch found out and quickly sailed to Bintan to set the record straight and renew their treaty.

Still Raffles and Farquhar didn’t give up, against their governments’ wishes not to go against the Dutch. In early 1819 they sailed to the Karimun islands, which they deemed too rocky for a port, then to Singapore where they met with the Temenggong who, disgruntled with the Bugis and the situation in Bintan, agreed to allow the British to start a small trading settlement. To legitimise the deal they brought in Hussain and made him Sultan of Singapore.

The Dutch made one last attempt to settle the dispute. In 1823 they took the regalia from Raja Hamidah by force and handed them to Sultan Abdul Rahman. But it was too late.

A year later the fate of the Malay world would be decided diplomatically on the other side of the world. In 1824 the Treaty of London was signed, where the Dutch and British cut the old kingdom in two.

The Malay world, so coveted by all with its central position on the crossroads between east and west, was cut in two. Everything north of the Singapore Straits, including Singapore and Melaka, fell under the British. Everything to the south, under the Dutch. The lines were drawn of what would later become the borders between Malaysia and Indonesia. And Raja Hamidah, the Bugis viceroys, the Sultans, the Temenggongs, none of them would be able to stop this.

A Bugis wedding and a famous writer

These days Singapore is one of the largest ports in the world, a crowded and wealthy metropolis. Bintan is a quiet yet peaceful island, in a forgotten corner of Indonesia. How did this happen? There are multiple reasons, but one story illustrates the fate of the Bintan port quite well.

In the early 1820s, before the dispute about the British settlement had been concluded, one of the Bugis chiefs on Bintan was getting married. To celebrate the happy occasion, a cannon was fired repeatedly. The Dutch, staying in Tanjong Pinang, heard this and thought the Bugis were attacking. They attacked right back, and raided the wedding, killing some of the guests. The Bugis chief and his people were so angry they packed up and moved to Singapore.

The British port of Singapore flourished quickly, due to the good trade relations of both Farquhar and the Temenggong, who later moved to Johor to become Sultan there after the British took sovereignty of the island of Singapore from him and Sultan Hussain in 1824. The Dutch kept quarrelling with the Bugis, many of whom moved their fleet and business to Singapore, and their local trade was a large contributing factor in the success of Singapore.

Even the Bugis viceroys moved their business interests to Singapore, though they kept living on Pulau Penyengat, which became an important intellectual and Islamic centre. Raja Hamidah’s nephew Raja Ali Haji became a famous 19th century scholar, historian and writer, celebrated across Indonesia. The power struggles continued and in 1911 the Dutch laid siege to Penyengat Island and took it, abolishing the Sultanate. The last Sultan and many remaining Bugis royals moved to Singapore. Bintan’s port slipped into oblivion, overtaken by the port of Batam which grew steadily from the 1970s onwards, due to its better position right next to Singapore.

The old Malay kingdom became three different countries. Its people remain, and its illustrious history should not be forgotten.